Take home messages

- Mid-row banding nitrogen fertiliser in-season was shown to increase uptake of fertiliser nitrogen in 2016.

- Trials conducted during 2016 and 2017 showed that mid-row banding can increase crop yield and/or protein in certain situations, but this effect was not consistent.

- Mid-row banding may offer logistical benefits compared with current methods of nitrogen application, but these should be considered against machinery cost, speed of operation and the ability to apply nitrogen inter-row in a specific situation.

Background

Studies over many years have shown that on average in Australia, less than half of the nitrogen (N) fertiliser applied is taken up by dryland crops in the year of application (Angus et al. 2014) with the remainder left in the soil for subsequent seasons or ‘lost’ to the environment. In‑season management of N fertiliser is also a key tool for managing variable seasons, however, when N is top-dressed as products such as urea, the risk of loss via ammonia volatilisation increases (Rochette et al. 2013) where rainfall is required to wash the fertiliser into the soil and enable crop access.

One option to reduce the risk of loss is to band N fertiliser below the soil surface. The concept of ‘mid-row banding’; where N is applied between every second crop row has previously been tested for N application at sowing (Angus et al. 2014, Lemke et al. 2009). However, with the advent of precision guidance systems, this study is investigating the potential benefit of mid-row banding during the season to better match the timing of N supply to crop demand, place N closer to where the crop can access it and reduce the likelihood of losses.

Aim

To assess the potential benefits of applying N fertiliser to wheat in-season by mid-row banding compared to conventional methods.

Paddock details

| Location: | Ultima and Longerenong |

| Crop year rainfall: | 324mm (Ultima), 424mm (Longerenong) |

| GSR (Apr-Oct): | 229mm (Ultima), 303mm (Longerenong) |

| Soil type: | Sandy clay loam (Ultima), Clay (Longerenong) |

| Starting soil N (0-1.2m): | 100kg/ha (Ultima), 198kg/ha (Longerenong) |

| Paddock history: | 2016 barley (Ultima), lentils (Longerenong) |

Trial details

| Crop type: | Kord wheat (Ultima), Mace wheat (Longerenong) |

| Treatments: | Refer to methods |

| Target plant density: | 130 plants/m² (Ultima) and 140 plants/m² (Longerenong) |

| Seeding equipment: | Knife points, press wheels, 30cm row spacing |

| Sowing date: | 24 May (Ultima) and 16 May 2017 (Longerenong) |

| Replicates: | Four |

| Harvest date: | 22 November (Ultima) and 29 November 2017 (Longerenong) |

Trial inputs

| Fertiliser: | Both sites received Granulock® Z @ 60kg/ha at sowing In season N applications: refer to methods |

| Chemical inputs: | Managed as per best practice to keep the trial weed and pest free |

Method

Two replicated field trials were sown using a complete randomised block trial design to assess the effect of a range of in-season N application methods on crop performance. Application methods included:

- mid-row banded at 35-50mm below the surface

- mid-row surface application

- streaming nozzle

- flat fan nozzle

- top-dressed.

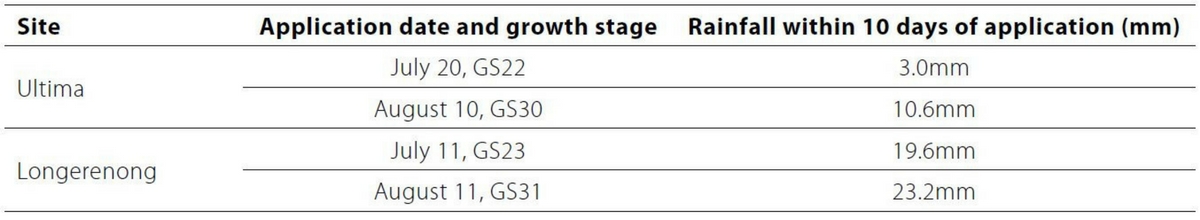

In-season N application occurred on two occasions at each site, the aim was to compare situations where N was applied prior to a rain front with situations where it was applied ahead of a dry forecast (Table 1).

All treatments were applied as liquid urea except where N was top-dressed when it was applied in granular form. Rates of N were 25kg/ha and 50kg/ha for all methods and dates of application with additional plots receiving either 15 or 100kg N/ha top-dressed on the first day of application to identify the overall yield potential of the site.

Table 1. Timing of N fertiliser application at Ultima and Longerenong, including crop growth stage and rainfall in the 10 days following.

Assessments included crop establishment counts, crop biomass at flowering and harvest, grain yield and quality. Additional sub-plots were established within the trial to measure the uptake of fertiliser by the crop in response to application method and timing. By using a ‘labelled’ form of urea, it was possible to directly track the proportion of fertiliser N present in the grain, straw and soil at harvest and thereby measure the proportion of fertiliser lost to the environment.

Results and interpretation

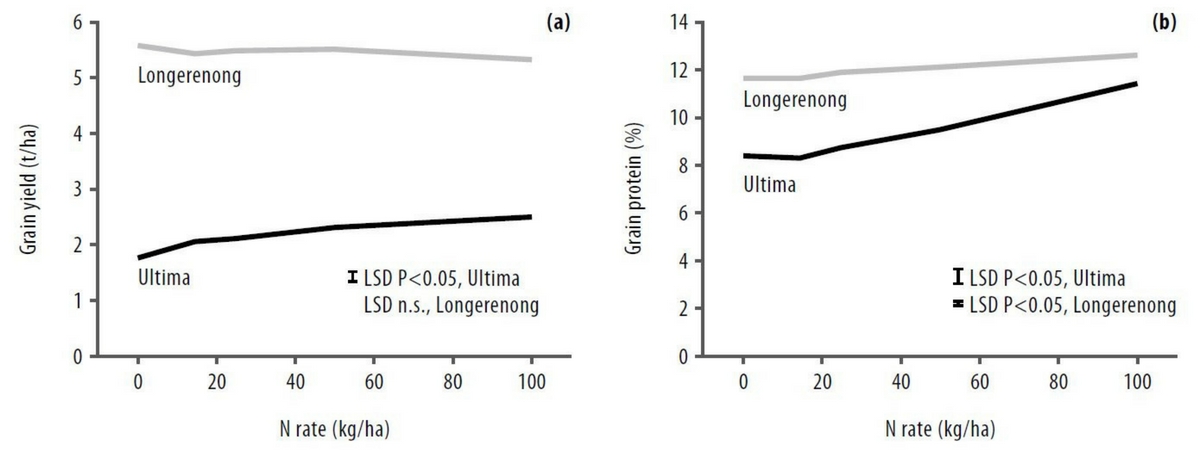

Seasonal conditions were favourable at Longerenong, receiving above average rainfall for the year. However at Ultima, conditions were drier, in particular during June-July (19mm) and September- October (24mm). As a result, yield potential at Longerenong was significantly higher (Figure 1). Despite moderate available N levels early in the year and the high yield potential at Longerenong, yield response to N application was limited. It is suggested that between initial site selection and sowing, a significant amount of N mineralisation occurred, resulting in high levels of available N at sowing, reducing the yield response. At both sites, a large proportion of available N was situated deeper in the soil profile (data not shown), it is therefore possible that drier conditions at Ultima reduced the crops ability to access this N, resulting in a greater N response at lower yields. Grain protein was responsive to N application at both sites; increasing from 8.4% to 11.5% at Ultima and 11.7% to 12.7% at Longerenong.

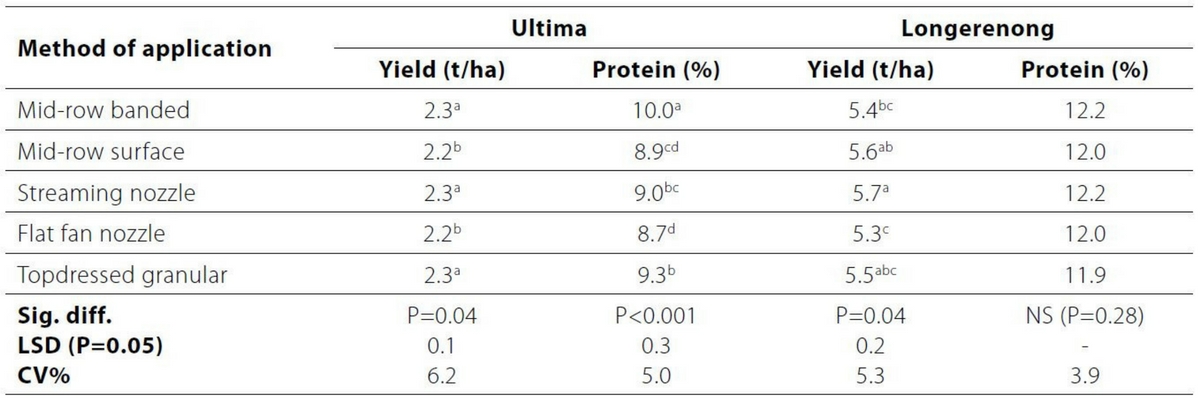

Method of N application had a limited effect on yield at both sites in 2017 (Table 2). At Ultima, mid‑row banding, streaming nozzles and top-dressed granular applications performed equally, yielding approximately 0.1t/ha more than either mid-row surface or flat fan nozzle applications. At Longerenong, results were more mixed with streaming nozzle the highest yielding while the flat fan nozzle treatment was lowest.

Grain protein increased significantly (0.7-1.1% higher) in response to mid-row banding at Ultima (Table 2) compared with all other methods of application. Similar to grain yield, application by flat fan nozzle resulted in significantly lower grain protein. Protein response to application method at Longerenong was not significant which was expected given the comparatively low response to N rate.

Table 2. Grain yield and protein response to N application method at Ultima and Longerenong in 2017. Values presented are the mean of both 25 and 50kg N/ha rates and both application dates.

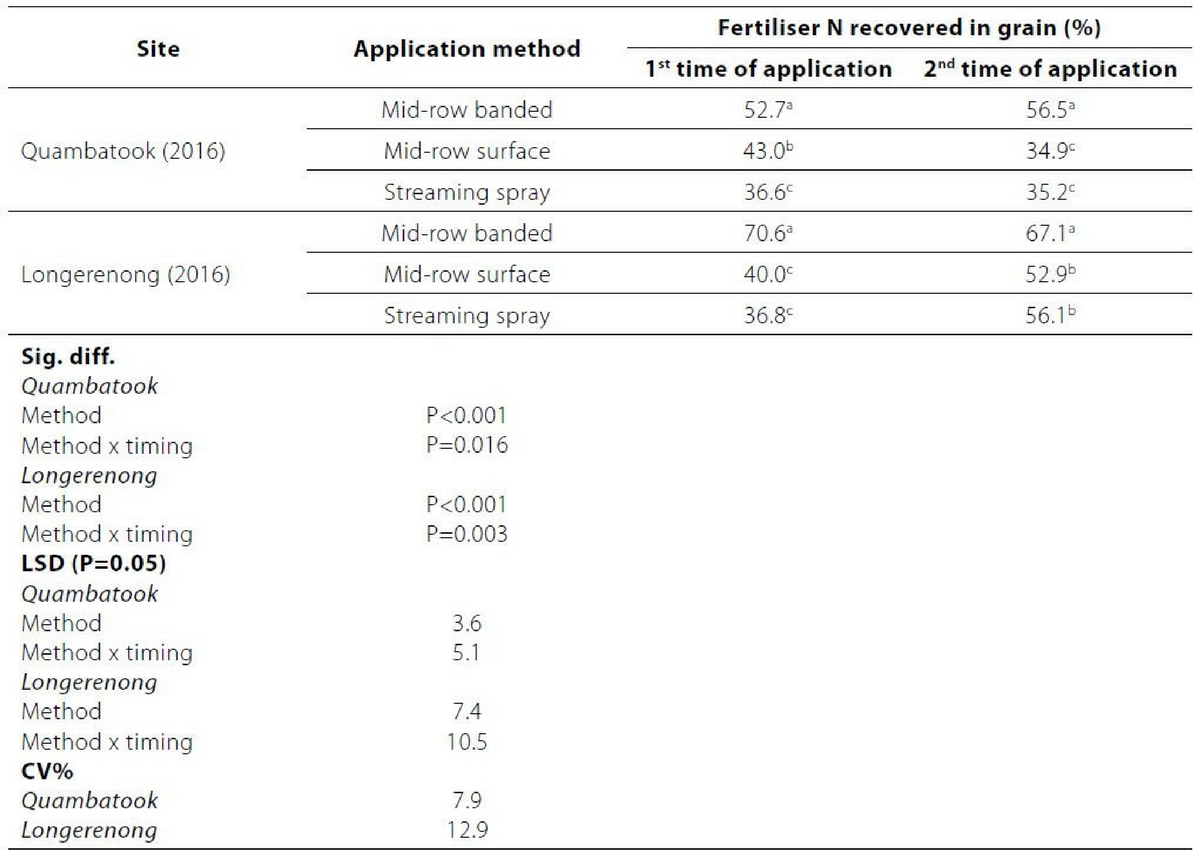

At the time of writing, data relating to crop uptake of fertiliser N was not yet available, however, results from similar trials conducted during 2016 showed that mid-row banding can significantly increase the proportion of fertiliser N recovered in the grain at harvest (Table 3). Similar to results in 2017, this increase did not always result in improved yields, although there was a positive trend from applying N in this way. Nonetheless, by increasing the proportion of applied N being taken up by the crop, mid-row banding significantly reduced overall fertiliser loss.

Table 3. Recovery of applied N in grain at harvest for various methods and times of application at Quambatook and Longerenong in 2016 (Wallace et al. 2016).

Commercial practice

Trials investigating mid-row banding in 2016 and 2017 have shown that applying N in this way may help to improve nitrogen use efficiency in certain situations. In 2016 there was a trend towards increased yields and crop uptake of applied N, while in 2017 at Ultima, mid‑row banding increased grain protein. The specific reasons for these observations are not yet clear. However, in situations where loss of N due to volatilisation of ammonia is an issue, banding N may help to reduce this risk compared with top-dressing during the season.

Applying this to a practical situation, mid-row banding may allow growers to apply N at times when they would normally wait for a forecast rain front, allowing for paddock operations to be spread across a wider window. However, the potential benefits should be weighed up against factors such as the relative cost of machinery to apply N in this way, the cost of fertiliser, the speed of operation compared to alternatives, possible effects of inter-row cultivation on weed germination and the ability to band between the rows at different row spacings and residue levels.

References

Acknowledgements

This research was funded through the ‘Improving practices and adoption through strengthening D&E capability and delivery in the southern region’, Regional Research Agronomists program (DAV00143) as part of the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC) and Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR), Bilateral Research Agreement. The authors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Birchip Cropping Group staff in delivery of the experimental program.