Take home messages

A mouse plague could still be on the cards for the 2018 season, and growers should be proactive about mouse management well before sowing begins.

Growers across the Wimmera and Mallee were hard pressed to stay on top of the problem in 2017 but mostly managed to avoid the severe and widespread damage generally associated with a plague.

However, with mouse plagues often developing over a two year cycle and current conditions

remaining conducive, the biggest threat could still lie ahead. Staying focused on effective mouse management is more important than ever.

The 2017 experience

Mouse problems in 2017 were little surprise after the bumper 2016 crop, long harvest period, and reasonable summer rainfall.

Demand for bait quickly outstripped supply and made it challenging for many growers to get on top of the problem early in the season. As well as widespread issues at sowing, reports from 2017 indicate that growers’ most advanced crops generally experienced the most substantial mouse damage.

Less damage was reported in late winter but other signs of mouse activity were still evident. With the onset of spring, activity was once again more obvious. Some growers resorted to baiting by plane to protect earlier flowering canola crops. Bait was effective in preventing damage throughout the season, but in some cases the cost of repeated baiting presented as much of a threat to profitability as the mice themselves.

Nevertheless, major damage was generally avoided by harvest, but decent yields, combined with the effects of wet weather over the harvest period, mean that the conditions are favorable for high mouse numbers to develop in 2018.

How does a plague develop?

Mice start to reproduce at six weeks of age, and can produce 500 offspring per year. This means that numbers can quickly explode when conditions are favourable. Mice begin breeding around September and continue for as long as good quality feed is available, with population peaks occurring four to six months after maximum feed availability.

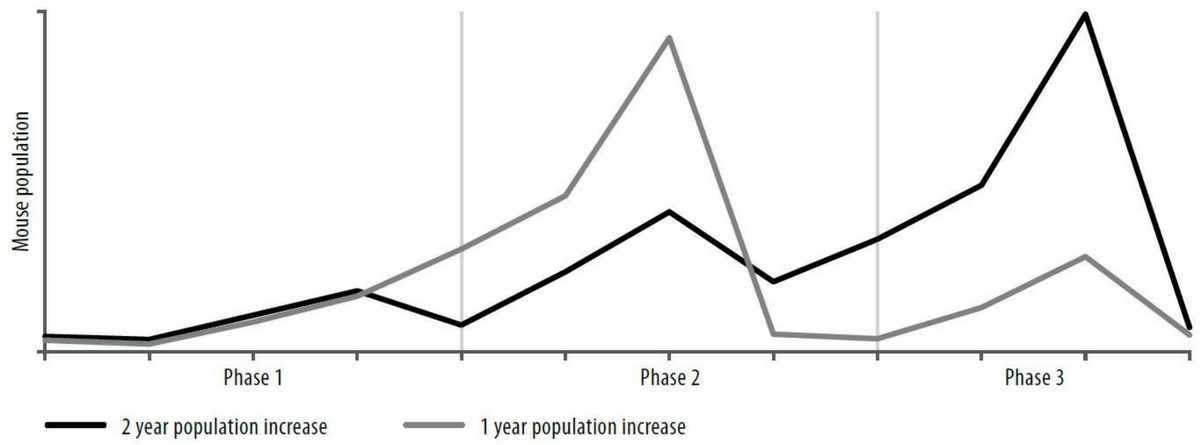

This means that a plague can actually take two years to develop, depending on seasonal conditions (see Figure 1). High stubble loads, dropped grain, and good spring or autumn rainfall provide extensive shelter and food that allow higher numbers to survive over summer and through to the following winter. Managing these risk factors is a year round job and will be key to reducing the risk in 2018.

Managing mice effectively

Effective mouse management is proactive and integrates activities aimed at reducing cover and feed sources, careful monitoring to stay ahead of the problem, and in-crop control when necessary. The GRDC has published a number of in-depth, useful grower guides on mouse management as part of project IAC00002 (see https://grdc.com.au/tt-better-mouse-management). Some key points are summarised below:

Keeping it clean

Good farm hygiene will reduce the amount of feed and cover available to mice. Simple activities like cleaning up spilt grain and keeping storage areas tidy can make a difference. Dropped grain at harvest can help sustain mouse populations through the summer period, especially when combined with heavy stubble loads, so grazing or other stubble management practices that reduce shelter for mice can help reduce the risk.

‘Keeping it clean’ also includes controlling weeds along fence lines and other areas close to the paddock. This may otherwise provide a safe environment from which mice can spread into crops. Even clutter around or near storage areas can give mice a safer place to live and multiply.

Monitoring

Mice are always present, but special care should be taken to monitor mouse numbers if you begin to notice unusual levels of activity or if conditions are conducive to an outbreak. Mice are generally considered to cause significant economic damage at numbers greater than 200 per hectare. At these numbers, they eat the equivalent amount to a single sheep and can consume 1% of a freshly sown crop per night (Stratford, 2010).

Inspecting crops for damage and counting active burrows can help you to determine when this threshold is reached. Mouse damage early in the season, or when they nip off the flowering parts, heads, or seedpods of growing crops, is often obvious. At other times of the year their effects may be easy to misidentify and it’s important to take a closer look.

In some BCG trial plots in 2017, canola that appeared to be at the early flowering stage was actually more mature, but had suffered from severe mouse damage. This was only obvious after closer inspection beneath the canopy. In wheat, dead heads may not be crown rot: mice may have chewed just above the nodes, denying the translocation of moisture and nutrients to the filling head.

To count active burrows, walk a 100m transect and count the active burrows within a one metre wide strip. If there are more than 2-3 (i.e. 200-300 burrows/ha) then a mouse problem is likely. At the BCG Main Field Day in 2017, CSIRO researcher Steve Henry offered a few tips to get the most out of this approach:

- Look for signs like spiderwebs or vegetative debris blown into burrows to indicate that they are inactive.

- If you’re uncertain whether it’s active or not, sprinkle cornflour in front of the burrow and check for mouse tracks the next day.

- Make sure you only count burrows that fall within the one metre strip – adding even one extra burrow can massively overestimate mouse activity.

Canola oil soaked chew cards are another common method of measuring mouse activity, but are not always reliable. As with burrow counts, a methodical approach delivers the best results: 10 x 10cm paper cards, printed with a 1cm grid, will give you a more objective view of mouse activity. Soak the cards in canola oil, and peg 10 cards at 10m intervals in a line 30m in from the edge of the paddock. Greater than 10 squares per card eaten by the next morning indicates moderate to high mouse activity, and more than 20 suggests a serious mouse problem.

In-crop control

Commercially prepared zinc phosphide bait is the only product available for in-crop broad scale control of mice. Bait is generally effective, but shouldn’t be relied on in isolation: early detection and a proactive approach to mouse control and management are critical to minimising damage.

A zinc-phosphide application rate of 1kg/ha provides 20,000 lethal doses per hectare. This is theoretically sufficient to kill mice even at plague proportions, but can be affected by factors like the availability of other, more attractive food sources (Brown et al. 2002).

Another major risk to the efficacy of in-crop control is bait aversion. Mice who consume a sublethal dose may avoid bait for 20-30 days (Parker & Hannan-Jones, 1996). At the 2017 Main Field Day, Mr Henry recommended a six week gap between applications to reduce the risk, at least in cases where the crop does not continue to sustain serious damage in the interim. Steve also stressed the importance of applying bait on as broad a scale as possible, and taking a coordinated approach with neighbours if possible, to avoid mice simply moving straight back in.

Make sure that you continue to monitor mouse activity after baiting to determine whether it has been effective or if further applications are necessary. It is critical to only use zinc-phosphide as directed on the label to avoid negative impacts on non-target animals.

What next?

The GRDC mouse monitoring project’s most recent ‘Mouse Forecast’, released in October 2017, suggested a moderate likelihood of an outbreak this Autumn. Whilst an outbreak is fortunately not guaranteed, actions taken today could help reduce the risk. With sowing just two months away growers need to stay vigilant.

Active management, such as grazing stubbles and good summer weed control, will help reduce mouse numbers before sowing, when an additional bait application can be applied. The only way to know if this is necessary is effective monitoring using the practices outlined above. Proactive mouse management may not pay off immediately, but could be a critical element for success in 2018.

References

GRDC, 2011, ‘Mouse Control Fact Sheet’

GRDC, 2017, ‘Tips and Tactics: Better Mouse Management’

Parker, R., Hannan-Jones, M., 1996, ‘The potential of zinc phosphide for mouse plague control in Australia.’ A review of literature prepared for the Grains Research and Development Corporation. Queensland Department of Natural Resources, Brisbane.

Stratford, G., 2010, ‘Mice Information Note’

Acknowledgements

BCG would like to thank Steve Henry (CSIRO) for his advice and expert knowledge in the development of this article.