Take home messages

Farmers make their luck by:

- concentrating on preventing losses, rather than depending on bonanzas

- giving priority to reducing costs, even if it means missing some income in good years

- diversifying markets (on-farm) and investments (off-farm)

Luck is the upside of risk. In fact, risk covers the full spectrum between disaster and bonanza. Understanding the factors that make the difference helps a farmer position himself at the positive (lucky) end of this spectrum.

According to the World Bank, Australian farmers face three to ten times greater risk than farmers in other competing countries. This being the case, if we are to compete internationally, it is vital that we manage risk. We must measure this risk and in so doing design systems which have the flexibility and resilience to cope with this variability. Our current systems lack this flexibility because their design is based on averages which, by definition, hide risk.

Farmers must understand the nature of risk if they are to plan to avoid it. Risk is uncontrollable. It is the opposite of certainty. It is expressed as a probability: the probability that applying fertiliser will be profitable (or not), or the probability that the new header will pay for itself (or not). An investment in either fertiliser or machinery is based on the farmer’s decision that it will improve his chances of increased wealth. Neither decision has a certain outcome; both may seem to propose an acceptable risk.

Current best practice is designed to maximise gross margins. Gross margins include only 30-40% of the costs of running a farm business. As the result of years of research into gross margins, the variable costs of running any particular enterprise have been refined to the point at which most farmers would find it difficult to reduce or change them significantly. The fixed and capital costs, which together account for 70% of farm costs (Figure 1), have largely been ignored, even though they account for most of the differences in financial performance between farms. Figure 1 shows that gross margins are only the tip of the iceberg.

Fixed costs are those associated with maintaining the farm and its workforce. They are called fixed, because they are not supposed to vary with the enterprise mix, but be constant for the business. In reality, they vary more than the “variable” costs between farms and farming systems. Machinery costs are an obvious example. The fuel, repairs, depreciation and financing of new machinery obviously increase with the area cropped, yet we do not usually include them in our gross margins calculations. Even telephone and electricity costs tend to be higher on cropping than grazing farms, probably partly due to the time spent in marketing (phone) and welding (electricity).

Figure 1: Diagram of farm cost structures (*EBIT = earnings before interest and tax)

Similarly, capital costs are higher for cropping, because of the costs of machinery. For instance, the purchase costs of satellite navigation are rarely included in the gross margin calculations used to justify the purchase. Capital costs also include living costs; if a farmer can’t make a living out of farming then it is a pointless exercise. This makes them the most important costs of all, yet they are never included in gross margins or profit, and rarely in cost-of-production calculations, because businesses are supposed to live off their profits. This is fine for big businesses, which deduct management costs before declaring a profit. Small businesses, including farming, cannot do this. Yet any small business which does not include living costs in its estimates will go broke.

This is a long way round to making the point that gross margins are dangerous. Farm decisions, and best practice, need to be designed to maximise cash flow (i.e. the bank balance) rather than gross margins. Managing risk to maximise cash flow is more difficult than managing risk at the gross margin level, because it includes more costs and more people.

Figure 2 shows the difference between gross margins and whole farm cash flows for a wide range of simulated farming systems in the MASTER trial near Ladysmith in southern NSW. Most of the treatments which showed positive gross margins would have resulted in losses if implemented on a farm. Planning based on gross margins can give very different results from planning based on maximising the cash flow. The important thing is to plan to avoid losses. Be conservative: plan for a drought but hope for a good year.

Figure 2: Comparing gross margins and cash surpluses

Risk and cash flow

There are two main ways of reducing the impact of risk on cash flow. These are by reducing costs, and by diversification.

Reducing fixed costs

Because farming is risky, the results of any spending are uncertain. The management decisions which reduce risk most effectively are those that work in the majority of years. The first and most important of these decisions is to reduce fixed and capital costs. Reducing these costs will have little effect on production, because production largely depends on inputs of variable costs (fertiliser, chemicals, seed etc.). Fixed and capital costs have to be paid for every year, even in droughts; reducing these costs increases the cash flow by the same amount in every year, regardless of rainfall or price.

There are two ways of reducing fixed costs. The first is to reduce the amount spent on any and all items. The second is to make the fixed costs variable, so that they become smaller in droughts, and are big only when the profit is also large. A typical example of this re-allocation of costs in farming is contracting. Contract costs are small when the yield is small; this contrasts with owning your own machinery, which will cost the same every year. Contracting effectively shifts the risk onto the contractor, and increases farmer margin in the lean years. This is important because losses accumulate and drive debt. Furthermore, using contractors frees up funds for more profitable investments. Big business managers know this, which is the reason that they sell their buildings and lease them back. Even though this may seem more costly, in reducing the risk of a loss, it improves long-term profit, releasing more money for diversification into more profitable ventures.

Diversification

The second way of reducing risk is to diversify. This can be done either internally by changing the farm enterprise structure, or externally, by changing the investment structure. The essential feature is that the diversification reduces risk, either by reducing costs or changing market exposure. Changing from wheat to canola is not a diversification, because the canola and wheat markets are closely linked and move in unison. Most farmers know that wheat yields are almost always twice canola yields, at half the price, which means that the returns are very similar.

An example of diversification, which is at the core of conventional mixed farming, is diversifying into sheep. This has several effects:

- Sheep are less costly to run, and limit the area sown to crop. Sheep reduce both the farm costs and the exposure to the higher risks inherent in cropping. As a result, sheep have the effect of lowering overall costs significantly.

- Sheep also limit the impact of low grain prices which reduce the costs of feeding them, thus buffering their downside effects on crop income. Pigs or chickens are even more beneficial in this area.

- Sheep, especially wool sheep, are sold into different markets which are almost independent of grain markets. Market research shows that only 22% of the variability in sheep and wool prices over the years is related to movements in grain prices. This effect buffers whole-farm income against losses in the crop enterprise.

- Wool prices tend to rise when production falls, because wool gets finer in drought years. As a result wool incomes are relatively static, regardless of rainfall.

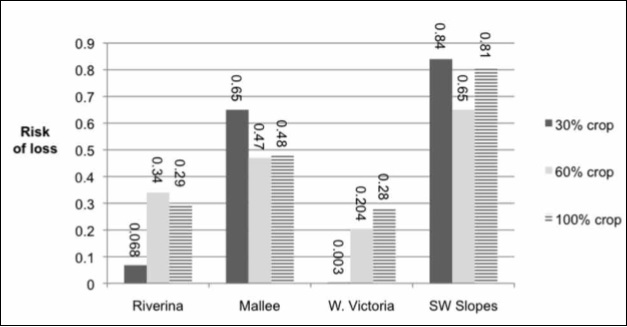

For all these reasons, sheep have proven to be an effective diversification over the years. Figure 3 shows how including some sheep (at normal prices) can reduce the risk of loss compared with continuous cropping on some selected mixed farms in eastern Australia.

The most notable difference between these farms is their level of spending: the Mallee and Southwest Slopes farms have higher fixed and capital costs than the Riverina and Western Victorian farms. On the high-cost farms the returns from sheep are less likely to cover the fixed and variable costs, increasing the probability of loss for the whole farm. The only way these farms can reduce their risk of loss is by reducing their costs. They are unlikely to be able to increase their productivity sufficiently to cover their high cost structure.

This point is particularly important. These farms are already very efficient producers and are unlikely to be able to increase their yields and stocking rates: these figures are based on yields assuming a 75% percent water-use efficiency. According to the international authority, Dr. Ken Cassman, this is about as high as most good farmers in developed countries average. He showed that the remaining 25% of water-use efficiency was lost due to uncontrollable factors like drought, frost and disease. These farms are already using all the rain; they are unlikely to be able to produce more, regardless of how much they spend.

Cattle are less effective than sheep as a diversification, because cattle sell into only one market, whereas sheep sell into three (wool, lamb and mutton markets.) Furthermore cattle, with a longer turnover time and traditionally (although not at the moment) higher cost per grazing unit, have a lower return on funds invested.

Buying machinery is one of the worst investments, because it ties up funds in a depreciating asset. Money used to buy machinery depreciates at about 12% per year, whereas money invested off-farm in shares appreciates at an average 7% per year. That is a difference of nearly 20% per year; effectively, the difference between the two investments doubles every four years.

Off-farm diversification can require lower levels of investment and risk; think of the long-term benefits of selling the cattle and buying Commonwealth Bank or BHP shares. Even bank interest, properly invested, gives constant rates of return above the normal levels generated by a farm.

Pita Alexander, a leading NZ accountant, encourages off-farm investment as a method of reducing the risk of loss on farms. His logic is as follows: if a farmer accepts a risk of loss every five years, and this loss averages say $50,000, then the farm needs to invest to earn $10,000 a year to cover this loss. If the off-farm investment averages a 14% return (average increase in the All Ords plus dividend yields and imputation credits), then the farmer needs to invest about $120,000 (allowing for compounding) off-farm, from debt-free profit, to insure against loss.

This is less than the cost of a small tractor and 25% of the cost of a header. It could easily be financed by selling either and used to insure the farm against loss. The same logic applies to debt reduction, which will show a compound return of 8-10% in the form of interest saving. Using surplus funds or money invested in assets with a poorer return will reduce risk and insure against loss. This applies to all low-returning assets, whether it is the unused machinery, the second house, the rocky hill paddock, the waterlogged gilgai country, or even the whole farm. Only hobby farmers farm to make a loss. Every successful business invests to grow their wealth, not their debt.

Figure 4: Effect of debt on the risk of losing money at the bank

Figure 4 shows the significant effect of debt (at 75% equity) on the risk of making a loss (on a typical Ardlethan or Urana farm) over any ten-year period since 1920. This graph also shows that including sheep in the enterprise mix reduces the impact of debt compared with continuous cropping, confirming the benefits of diversification, especially when the debt is under control. When debt is high, then the farm is more likely to make a loss, regardless of the farming system.

Conclusion

Farmers get lucky by concentrating on preventing losses, including

- reducing their fixed costs, including interest costs

- diversifying their markets

- diversifying their investments

- getting rid of non-performing assets

All these issues reduce the risk of loss and increase assets. None of these issues is new, and all are common to every successful business. The trouble with farming is that we have become so obsessed with growing plants and animals we have forgotten how to grow our wealth, which is the main game.

Acknowledgement

This paper was first presented to the Farm Link Mixed Farming Conference at Temora on 12th August, 2011 and is presented with their permission.